Robert Carlson, a fan of my books as a child and now a film major in college, wrote recently asking if I've read a book called Floor Games by H.G. Wells. As it happens, I have a 1931 edition of it on my bookshelf (originally published in 1913), and the question prompted me to revisit the slim, illustrated volume dedicated to the art of playing. Yes, that H.G. Wells, the writer of The Time Machine (1895) and The War of the Worlds (1898), and now regarded by many as the father of science fiction. Here, he's the play-loving father of two sons, regaling us with the "infinitude of imaginative games" he shares with them. He's the impresario of miniature world-building, providing detailed advice on toys and materials, beginning with that most essential element, the floor:

"The jolliest indoor games for boys and girls demand a floor, and the home that has no floor upon which games may be played falls so far short of happiness."

Floor Games, by H.G. Wells

There are no rules for these kinds of games. This is free-associative world-building, but he does hint at ways to keep the peace among the players: "We distribute our boards about the sea in an archipelagic manner. We then dress our islands, objecting strongly to too close a scrutiny of our proceedings until we have done." In another chapter entitled "Of The Building of Cities" he writes, "We always build twin cities" because both sons want to be "lord mayors and municipal councils."

It's of particular interest to me that the book is photographically illustrated. Text pages contain whimsical drawings in the margins by J. R. Sinclair. There is no photographer credited but it appears to be Wells himself behind the camera: "As I wanted to photograph the particular set-out for purposes of the illustration of this account, I took a larger share in the arrangement than I usually do."

Floor Games, by H.G. Wells

In a close-up photograph of the "Wonderful Islands" (above), Wells playfully notes his sons' Plasticine monsters guarding a temple, calling them "remarkable specimens of Eastern religiosity," but then adds, "They are nothing, you may be sure, to the gigantic idols inside, out of reach of the sacrilegious camera." And with that, he gets to the very essence of imaginative play, when the deep recesses of the creative mind conjure images no toy could hope to emulate; no camera could hope to capture.

Floor Games, by H.G. Wells, drawings by J.R. Sinclair

While the Wells family floor games are accessorized with toy soldiers, figurines, wind-up train sets, miss-matched farm animals and other store bought items, Wells is disparaging of the "incompetent" toyshops. "We flatten our noses against their plate glass perhaps, but only in the most critical spirit." He preferred an over-sized collection of large wooden "bricks" procured from a Good Uncle who Wells praises far above the "common levels of humanity" (see statue erected in his honor above). Wells then goes on to describe in detail the dimensions of the components, including sets of full, half, and quarter size blocks. He also describes the various sizes of wooden boards and planks he had fashioned to complete the modular system.

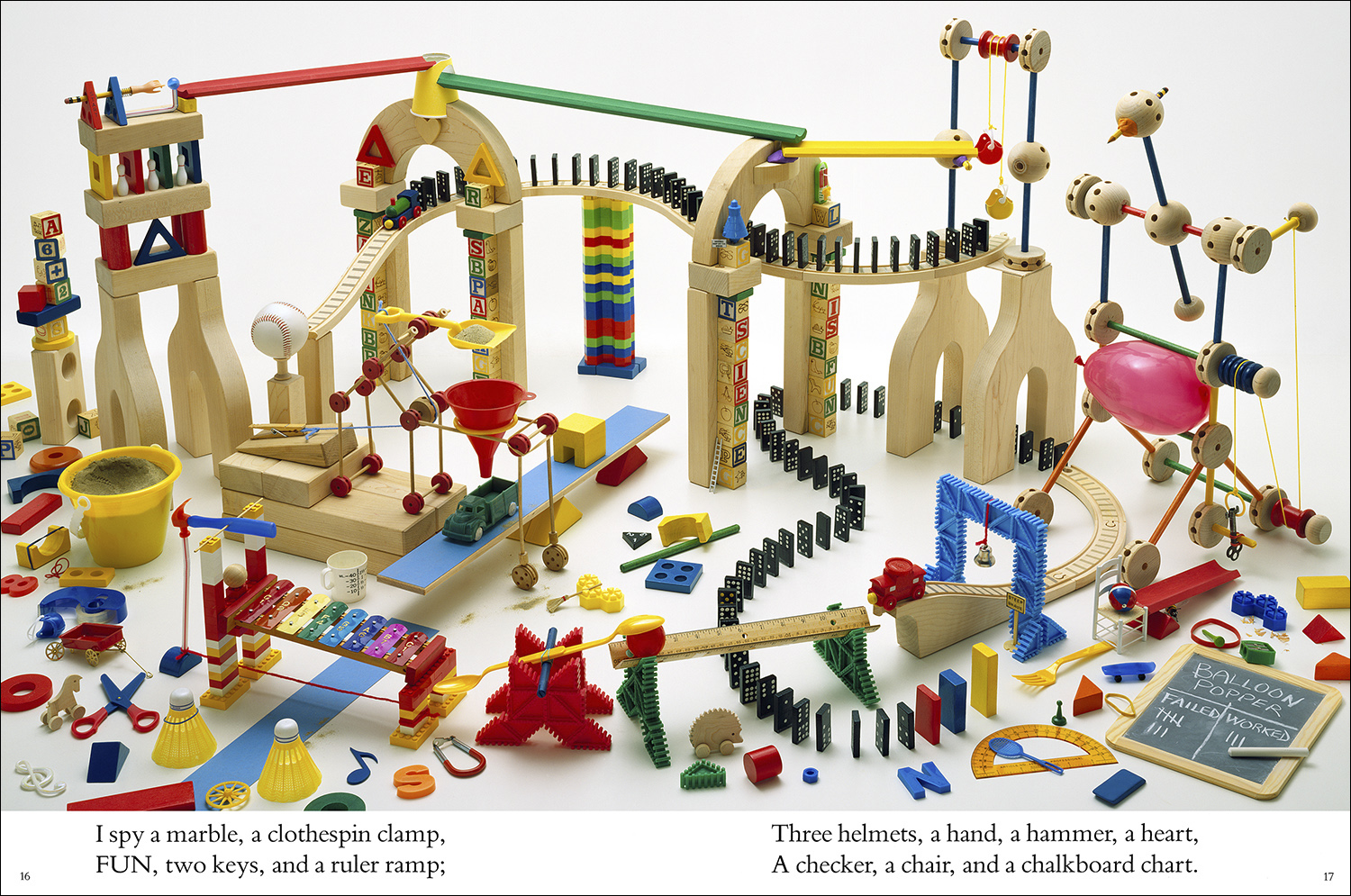

Chain Reaction (detail), from I Spy Mystery (1993), Photographs by Walter Wick, Riddles by Jean Marzollo

Those familiar with my photo illustrations would know that "floor games" are a frequent theme. Others familiar with educational toys would recognize that Wells' "bricks" are a precursor to "unit blocks" - the plain maple blocks often found in pre-school classrooms. However, it was not due to Wells that unit blocks first came into my studio. That distinction belongs to another advocate for imaginative play, Jean Marzollo. It was Jean who recommended I use them for a back-to-school themed poster for Let's Find Out, a kindergarten magazine she edited at the time. When we later collaborated on the I SPY books, the blocks followed, along with their many benefits. Because the plain wooden shapes lack any prescribed function, they can become the building blocks for virtually anything – a castle, a multi-tiered toy-car traffic jam, even a machine that pops a balloon.

City Blocks, from I SPY Fantasy (1994), Photographs by Walter Wick, Riddles by Jean Marzollo

Levers, Ramps, and Pulleys, from I SPY School Days (1995), Photographs by Walter Wick, Riddles by Jean Marzollo

The long, extended play sessions of my youth were essential to the creator I am today. It helped exercise those world-building and problem solving pathways in my brain, and in turn enabled access to those deep recesses of the creative mind. Like learning a second language, it sinks in more thoroughly when you start young. I'm thrilled that the college-aged Robert Carlson, who only recently discovered Wells' opus to imaginative play, recognized the kinship to the I SPY books of his youth. I was even more thrilled to learn I SPY helped inspire Robert and his siblings to create long-running "floor game" adventures of their own – with some even utilizing the roof! You can see them for yourself on the YouTube channel he still maintains. Thank you, Robert, for inspiring me to revisit Floor Games!

Video by 5MadMovieMakers